What Interviewing a Suspected Serial Killer and His Victims Taught Me About Empathy

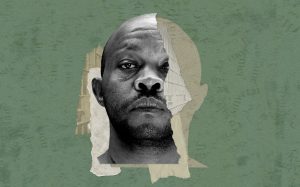

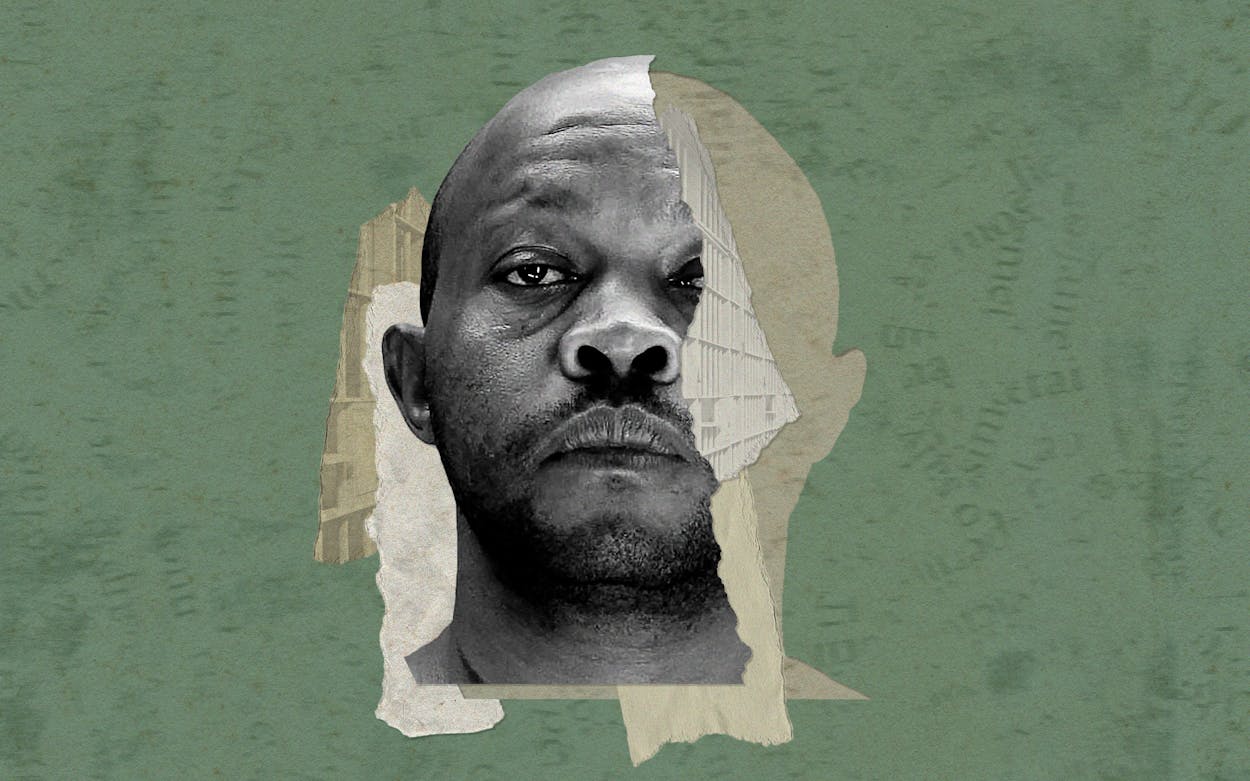

Spending three years reporting on Billy Chemirmir, who was charged with multiple counts of murder around Dallas, was a daunting experience I now use to instruct future journalists.

The first time he called, I was home with family on a Saturday afternoon in 2022. I asked if he had time later to continue our conversation. “Yeah, I have nothing planned,” he laughed.

It was a funny line. His name was Billy Chemirmir, and he was in the Dallas County jail awaiting trial on eighteen counts of capital murder. Just a few months earlier, his first trial had ended in a shocking mistrial. Of course he had time. It wasn’t like there were pressing appointments to schedule around while he was incarcerated.

I’d been covering the case against Chemirmir for three years as a reporter for The Dallas Morning News. He’d been accused of stalking elderly women at luxury senior living communities in the Dallas area, posing as a maintenance worker to get access to their apartments, smothering them to death with a pillow, and then rifling through their personal belongings so he could steal their cash and jewelry. He had been linked to two dozen deaths in all.

Most of my reporting on the case has centered on Chemirmir’s victims—the children and grandchildren left behind. In my new podcast about the case, The Unforgotten: Unnatural Causes, which launches in October, I dive into systemic issues of ageism and corporate greed that created the loopholes Chemirmir used to target his victims. These are difficult conversations, ones I approach with patience. When I first reached out to Shannon Dion, whose mother Chemirmir was accused of killing, she was extremely distrustful of the press and did not want to be interviewed. I respected that, and gave her space. Over time, I’d check in to see if she’d be more prepared to answer some questions about her mother’s life—not just her death. Eventually, she invited me to her home for several long conversations. I went with her to church, and to the courthouse, and to Austin, where she lobbied for stronger security measures at senior living communities statewide.

Today, Shannon and I are very close. She is one of my annual guest speakers in the journalism ethics classes I teach at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. She tells my young reporters that interviewing victims of trauma is more than just asking the right questions. It requires moving slowly and handing over control of the interview to the victim—a power shift many reporters are hesitant to give up.

Shannon and I teach young journalists what the scholar Janet Blank-Libra calls “an ethic of empathy in journalism.” We show them how to handle those difficult conversations with care, and how to prioritize their own mental health while on assignment. Covering violence means being exposed repeatedly to potentially traumatic stress, so I tell students about the times where I needed time and space, too.

During Chemirmir’s first trial, a few months before he called me, I arrived at the Dallas County courthouse every day before sunrise and left long after sunset. The long days, plus the hours of standing in the press pool and sitting on hard benches, had me exhausted by the time the judge declared a mistrial. The whole thing ended without a real conclusion. Chemirmir couldn’t be found either guilty or not guilty.

After covering the case for so long, I broke down. I found an empty stairwell in the courthouse, and cried, trying to get myself together to finish writing that day’s news story. I decided to step away from the case for a while and find something new to write about. That’s when Chemirmir called me, wanting to share his side of things.

I’d spent years devoted to telling my readers about the mental and emotional scars these murders created. I wouldn’t be doing my job if I didn’t give Chemirmir a chance to comment on his own case. I believed the evidence against him was strong, but I’ve been wrong before. I’d approached his victims with care and empathy. I had to try to offer him the same.

Empathy is a precursor for compassion, but it doesn’t always lead to it. Being an empathetic interviewer doesn’t mean sidestepping tough questions. Empathy demands accountability.

In my first extended conversation with Chemirmir, I laid out all the evidence against him. Security camera footage of him entering and exiting the senior living properties. Cellphone records showing he was in the area. Online sales records showing him selling the stolen jewelry. His DNA at the crime scenes, and victims’ DNA in his car. I told him that if I were to believe him, he would have to be the unluckiest man on the planet, to have been in the wrong place at the wrong time over and over and over.

He dodged, pivoting to complaints about the prosecution’s witnesses and his own defense team. Whenever I’d bring up specific cases or specific evidence against him, he’d employ a tactic used by people who know the facts are against them: Don’t answer the question. Deflect. Avoid providing evidence for claims.

Getting the story right means asking for details and corroboration. When I ask trauma victims for those things it isn’t to belittle their experiences or signal that I do not believe them; it is done to make sure that I’m telling their story as completely and accurately as possible. Being a good steward of that story means getting it right.

In subsequent trials, Chemirmir was convicted of two counts of capital murder, and received two sentences of life without parole. He called me again a few times after that second conviction. His story then was much the same as it had been. He was innocent, he said, but had no reasonable explanation for the mountains of evidence against him.

He was serving his sentences in an East Texas prison when, one year ago on September 19, he was stabbed and beaten to death by his cellmate. He bled out overnight on the prison floor. His body wasn’t found until the next morning.

But while the killer is gone, the trauma he left behind lingers. I could never understand what he was thinking as he killed his victims. Just like I could never understand what it’s like to learn that your loved one was murdered by such a man.

Instead, through empathy and patience, I ask those who do understand to help me explain the consequences of that trauma to others—to tell their stories, with care and compassion.